2015/12/28

Books of the Year

It's that time again: all and sundry are putting out their end of year polls. To cut through the morass of talking heads taking us through stuff we've already seen, have a look at the 'books of the year posts' over at Wormwoodiana. I'm happy to have been able to contribute along with the fine writers and readers associated with Wormwood.

2015/10/31

Wormwood Article

I have an article in the new issue of Wormwood, the journal of fantastic, supernatural and decadent literature. Titled 'Notes on the Modernist Ghost Story', the essay looks at the various liks between the early 20th century ghost story genre and what might be termed the 'canonical' works of 'high' literary modernism. My thanks go to Mark Valentine for offering me a spot in the issue. I'm deeply indebted also to him for the kind words he posted about the article on the Wormwoodiana blog:

I have an article in the new issue of Wormwood, the journal of fantastic, supernatural and decadent literature. Titled 'Notes on the Modernist Ghost Story', the essay looks at the various liks between the early 20th century ghost story genre and what might be termed the 'canonical' works of 'high' literary modernism. My thanks go to Mark Valentine for offering me a spot in the issue. I'm deeply indebted also to him for the kind words he posted about the article on the Wormwoodiana blog:"The ghost story: an old-fashioned form; its finest writer an antiquarian. A thing of graveyards and cloisters, steeped in tradition. Surely it simply “wallows in the nightmares of history”?

Not according to Cambridge academic James Riley, who opens our new issue with his ‘Notes on the Modernist Ghost Story’. It’s time to acknowledge a different approach:

“…the figure of the ghost, theme of haunting and the presence of the supernatural are not concepts alien to ‘high’ modernism. Woolf opened her collection Monday or Tuesday (1921) with the story ‘A Haunted House’ which later became the title of her posthumous collection A Haunted House and Other Stories in 1944. Consider also Leopold Bloom’s reflections on communication with the dead in Ulysses, and the spectral image of London as an “unreal city” that pervades ‘The Waste Land’.

"Mary Butts used similar imagery in ‘Mappa Mundi’ (1938) when describing the “matrix” of dream and physical experience that constitutes “Paris and the secret of Paris”. Occupying the ghostly position of that which is there and not there at the same time, the city is compared to the face of Isis glimpsed during an initiation. Similarly, in ‘Mysterious Kȏr’ (1942), Elizabeth Bowen appropriates the fabulous city of H. Rider Haggard’s She (1887) to present wartime London as a “ghost city”."

But his essay doesn’t just broaden our image of the ghost story. James Riley also argues that M R James himself uses modernist concepts, especially in his treatment of time. The distinction between the classic and modernist ghost story may not be reliable."

Wormwoodiana currently features blog posts on each of the articles in the current issue. Check it out for details on essays on Sarban, David Lindsay and Guy Endore.

2015/09/07

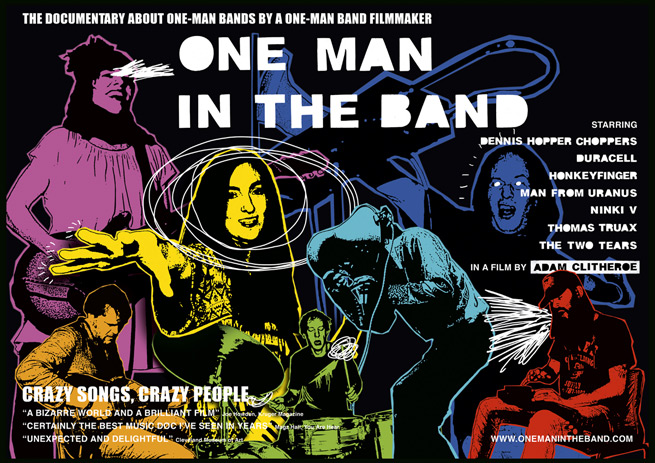

Better Alone: Adam Clitheroe’s One Man in the Band

"One-man bands. Showmen, eccentrics, loners. This documentary follows a selection of contemporary musicians who play as one-person acts and discovers that, for them, music just sounds so much better when you make it all alone. Featuring musicians from the UK, France and USA and an awesome array of instruments ranging from theremins through to drum machines built from bicycle wheels, the film reveals the struggles that the performers have in balancing their public and private personas. As the music becomes ever more flamboyant and eccentric, so they find themselves retreating into loneliness and solitude. This is a moving and humanistic study of why people choose to be creative, filled with memorable musical performances, and achieving real intimacy between the one-man band filmmaker and his subjects."

It's obvious to me in retrospect that the subject was attractive because I was wondering if I'd ever make a film again, and whether I should bother. It's being drawn towards that mirror which, when you look into it, you'll be able to say "this is who I am". I hadn't thought about the film much more than that when a music promoter friend introduced me to Man From Uranus in a pub. He's this legendary one-man band, a Gulf War veteran from Florida washed up in the Cambridgeshire countryside who makes deeply eccentric music which sounds like Stockhausen writing kids' TV theme tunes. Plus he plays the theremin while wearing wellington boots on his hands. He invited me to a children's birthday party the next weekend and so the filming began. That's the great thing about the independent music scene - there's a real energy of "don't talk, just do it". On the other hand, independent filmmaking can be paralysed by procrastination - you don't want to piss away years of your life and bankrupt yourself by embarking on the wrong project.

AC: There are seven one-man bands in the film, three from the US, three from the UK and one from France. But I'm based in London which is one of the live music capitals of the world, so I picked up on most of them when they were passing through. I filmed on and off for around six months, for a few days here and there, travelling with them around the UK and in France. I'm not one of those American independent documentary makers who shoots hundreds of hours of footage and then has to employ a story consultant to make sense of the mess. I'm a lazy Englishman who filmed minimally for few evenings and weekends. As I said, I embarked on it with little thought about what the film would be. After I had a few weeks of filming under my belt the paranoia of what the hell was I doing started to kick in. Most of what I had shot had been filmed over a particularly grey and pallid winter, which sort of became an eighth character in the film, so it seemed appropriate to stop before spring kicked in, and to figure out what I had got.

AC: The film was all shot on a handheld progressive scan, square screen DV camera. My background is in 16mm filmmaking, and these video cameras give you results a bit similar to filming on Bolexes. The quality is not brilliant, but it has a texture and fluidity that is right for the subject. Plus you can fling the camera around without worrying about it too much. Portability of camera gear is an important consideration when you're filming a zero budget movie like this. Thomas Truax, a New York one-man band in the film, summarises it well. He builds elaborate mechanical instruments such as the Hornicator and Sister Spinster and uses them as surrogate band members. But if they don't fold up and fit in his suitcase, he can't get them on the train so he can't afford to tour so that's him finished as a solvent musician. Same for filmmaking.

AC: While I was editing the film, I read an interview with Mike Skinner, aka The Streets, in which he said he never mentioned specific locales in his songs because he wants them to appeal to people everywhere. If you have a caption on screen saying "Sheffield, 1am", whether you like it or not, you've focussed your audience's attention on a parochial narrative. If you're depicting an event of global significance, fine, time and date it, but if it's Thomas Truax locked out of his hotel room, don't. I like to think of the film as a frame of mind... it's a way of thinking that exists anywhere, anytime. Plus, the life of a one-man band is seemingly aimless... playing some small venue, packing up and drifting to the next town for the next gig. Identifying this meandering route would glamorise life as having some sort of structure and narrative.

One Man in the Band (2008) is one of the great cult music documentaries of recent years. Adam Clitheroe's heroic documentary sheds light on a fascinating musical underworld of sole performers playing on the hinterlands of the live circuit. In addition to featuring great music, it's an unexpected portrait of artistry and isolation. It's also a film that's capable of launching a thousand obsessions. When you see it, you'll find yourself scanning the gig listings, trying to track down some of the performers. The film has just had a digital re-release via Gumroad. Check it out. In the interview below Adam spoke to me about the process of making the film, the people who feature in it and the strange world he was granted acess to.

James Riley: How did the film come together?

Adam Clitheroe: The film, like many independent projects, arose out of desperation. I'd spent a few years trying to get feature documentaries off the ground. I wasted one summer waiting in fields in Mexico, hoping to meet friendly smugglers. Another time, I went to the Berlin Film Festival for meetings with Nigerian producers, which to my bemusement led to a hard cash offer to make a feature of my choosing. Naturally, the producers went back to Lagos and I never heard from them again. As time went on, the films I was trying to make became smaller and more adaptable to circumstance.

I became interested in making a documentary about performance - the idea that some people are driven to live a life of hard work and abstinent suffering, in return for a few moments of sublimation through performing. It seemed to be the flipside to the 'easy' celebrity culture that was dominating consumer media at the time - the idea that incredibly talented performers were trudging through a long dark winter of the soul, obscure and unremarked yet unwilling to give up on their ambitions. One-man band musicians seemed to be the purest embodiment of this sort of performer. Not novelty buskers, but people who take to the stage alone and compete with conventional bands at their own game, not compromising in the 'full band' sound even though they are solo. Can you name any famous, stadium-filling one-man bands? There are no household names. But there are hundreds of contemporary one-man bands out there working the circuit. Put some of them in a film and you're not going to end up with a celebration of acclaimed musical geniuses, but rather something more democratic: you've not heard any of these artistes, you listen to them and you decide whether or not they are any good.

Adam Clitheroe: The film, like many independent projects, arose out of desperation. I'd spent a few years trying to get feature documentaries off the ground. I wasted one summer waiting in fields in Mexico, hoping to meet friendly smugglers. Another time, I went to the Berlin Film Festival for meetings with Nigerian producers, which to my bemusement led to a hard cash offer to make a feature of my choosing. Naturally, the producers went back to Lagos and I never heard from them again. As time went on, the films I was trying to make became smaller and more adaptable to circumstance.

I became interested in making a documentary about performance - the idea that some people are driven to live a life of hard work and abstinent suffering, in return for a few moments of sublimation through performing. It seemed to be the flipside to the 'easy' celebrity culture that was dominating consumer media at the time - the idea that incredibly talented performers were trudging through a long dark winter of the soul, obscure and unremarked yet unwilling to give up on their ambitions. One-man band musicians seemed to be the purest embodiment of this sort of performer. Not novelty buskers, but people who take to the stage alone and compete with conventional bands at their own game, not compromising in the 'full band' sound even though they are solo. Can you name any famous, stadium-filling one-man bands? There are no household names. But there are hundreds of contemporary one-man bands out there working the circuit. Put some of them in a film and you're not going to end up with a celebration of acclaimed musical geniuses, but rather something more democratic: you've not heard any of these artistes, you listen to them and you decide whether or not they are any good.

|

| Man from Uranus |

JR: I guess some of these ideas fed into your own 'one man band' filming approach?

AC: Choosing to make the film entirely as a one-man band filmmaker was part of the process of subject and filmmaker finding reflection in one other. I had no funding so my initial worry was that I couldn't afford multiple camera shoots for live music scenes. I figured that if I filmed one-man bands, I would only need one cameraperson - myself. Plus I was very much aware that I had to gain the trust of the musicians in the film - they were allowing me to use their intellectual property of songs and performance. Approaching them as one well-meaning but slightly disorganised filmmaker meant that we found common ground very quickly and could share the chaos together. There is a slight paradox in that most of the one-man bands in the film are quite shy people - they can take the stage and wow a room of people, but strip them of their music and instruments and most of them want to evaporate. It's personal relationships that make interviews possible in these circumstances, and even if I could have afforded a film crew, it would have been a hindrance.

The other influence on the one-man band filmmaking approach was a 16mm short film I made beforehand, called Harder Faster Stronger Stripier. It was about my neighbour, an eccentric painter who is almost an outsider artist. The film was a curious observational piece, a skewed reflection of his world and a space for him to talk on his own terms. I think it had the same combination of the subject's hermetic creativity and idiot gaze of my camerawork that is found in One Man in the Band. It's one of my favourite short films I made. But only four people have seen it. We had the premiere in his front room, it was one of the most successful premieres I have ever had.

JR: How did you decide which artists to focus on?

AC: There are a lot of one-man bands out there, playing every genre of music imaginable. The first challenge is to figure out what you mean by 'one-man band'. It's a catch-all term, but you wouldn't refer to Bob Dylan playing his guitar and harmonica as a one-man band. So is it to do with the number of instruments you play live at the same time, or is someone strumming along to a backing tape also a one-man band? I figured that doing some sort of taxonomy of one-man bands would not make a very interesting film, so for me it became more important to find those people who, in their own minds, are one-man bands. They might not use the actual term, but they think of themselves as full bands and take to the stage to celebrate the joys of noise accordingly.

That principle established, it was a case of hanging out in lots of backstreet gigs and seeing which one-man band performers clicked for me. If you have seen someone play and you have seen something deranged and magical and unique and exciting in what they do, that motivates you to introduce yourself as a filmmaker and persuade them that you have something to offer back. So I guess that the people who made it into the final film were the ones I liked a lot as people and felt a personal connection. The only limiting factor was that some one-man bands are permanently touring and I couldn't afford to keep up with them. I would have loved to put Bob Log III in the film. He's this insanely fast slide guitarist from Arizona who wears an Evel Knievel jumpsuit and a motorcycle helmet with a telephone receiver glued to it. I filmed a gig with him at the Spitz in London and he drove the crowd into a baying mob - incredible. But then he was out of the country the next minute and I had no cash to follow.

One slightly disturbing aspect was that, as shooting progressed, it became clear that the majority of musicians I was filming had very tumultuous personal lives and were in the process of divorcing and separating. I wasn't aware of this beforehand, but when you build this intimate one-on-one relationship with your subject as filmmaker, you become privy to all sorts of personal stuff. Since all this pain and anguish seemed to fall in the brief period for which I was filming, I became worried that I was a bit of a jinx. But really, I think that for some of the musicians, the fact that they were having a rough personal time was subconsciously why I was attracted to filming them. There's this sense of wearing your nerve endings on the surface, of your emotions having been roughly sandpapered, that gives you this peculiar intensity and clarity in the way you present yourself. I don't think it's necessary to be jilted to be a successful one-man band, but that trauma perhaps amplifies certain traits of driven loneliness shared by one-man bands. After all, throwing yourself into your art absorbs the pain of separation.

JR: Could you sketch out some of your working methods? How long did the shooting take? How long did you spend travelling with the artists?

|

| Ninki V |

I did try to film the rhythms of life for the one-man bands. Because I didn't have prescriptive ideas I was trying to project into the film, it seemed appropriate to film whatever they were doing when I was with them, regardless of the banality. I didn't want the movie to be a series of highly structured talking head interviews, but then realised I had to interview them a little bit as they were alone on camera and they wouldn't talk at all otherwise. So the film is a series of offbeat chats on location, interspersed with the debris of everyday life. I especially like the scenes with some of the artistes such as Ninki V and Dennis Hopper Choppers in their homes. Someone else's domestic interior is your own vision of insanity.

One of the weird things in the editing of the film was the complete eradication of myself. While shooting, I hadn't really decided whether I would be in or out of the film as an off-camera presence. But because the film in post-production became quite strongly an atmospheric piece, being aware there is always someone else present in the scenes became a distraction. So I faded away and became invisible, like those figures in Soviet history airbrushed out of photographs. All that is left of me is the idiot gaze of that camera and an occasional eccentric spasm of editing.

JR: Man From Uranus seemed to be the fulcrum of the film. Was this because you found him perhaps the most interesting?

AC: Man From Uranus plays a pivotal role in the film. All of the seven musicians are very different personalities and play very different music, ranging from growling blues stomp to hurricane drum solos. But it’s safe to say there's no one else like Man From Uranus in the musical firmament. He plays a range of antiquated analogue electronica from theremin to reel-to-reel, producing a sort of bastardised lounge music on steroids. I think he represents an important aspect of one-man bandship because he's the one who most overtly considers music-making an artform, placing himself in the role of brilliant but odd outsider artist. Indeed, his antics with wellingtons and beep hats make perfect sense as performance art. On top of that, he is incredibly eloquent about his upbringing in the States by libertarian hippies and doom-mongering Baptists and his traumatic experiences in the US military. His musical journey represents some sort of quest for self-worth on his own terms. In the film, he represents the shift from presenting these weird and wonderful one-man bands as entertainers to a more searching questioning of what is it in the human condition that drives some people to be creative. Plus, he's a lovely guy who wears slippers all the time, even in winter snowstorms.

JR: Couple of technical questions: because you were working on your own what was your set up? What type of camera did you use and how did you approach recording the live sound at the concerts you shot?

|

| Duracell |

Recording live sound at the concerts was an extreme challenge. Usually there's an array of sound engineers making sure the audio is good for music television, whereas I was on my own, filming, taking stills and getting legal releases all at the same time. I'd turn up with the musicians to sound check, try and persuade the venue sound people to let me have a feed from the mixing desk, and then get another microphone set up in case that sound screwed up during the performance. A lot of these one-man bands are insanely loud... I think it's part of the compensation for being just one person on stage. The French drummer Duracell triggers synth loops from switches around the edges of his drum kit while he drums in the style of Animal from the Muppets. The amplifier he uses was liberated from a Meat Loaf tour in the 70s, and he produces this overwhelming tsunami of noise. The best way for me to get something useable was put a radio clip mic on him and put as many plugs as possible into my own ears so I could get close enough to film.

Having said that, I think it's far better to have the 'raw' music recording in this film than the over-sanitised live music you hear on TV which sounds like it's coming off a CD. Live music should sound live, and as Honkeyfinger said to me after hearing his swamp rock in the film, if it's gnarly that's a good thing. I think it's an important part of the one-man band experience that mistakes and blemishes become part of the performance. There are no other band members to hide behind, it's just you and the audience, and audiences tend to be much more forgiving of errors than they might be for a full band. In the same way, I left a lot of 'blemishes' in the film edit - wildly expressionistic camera zooms, an inexplicable fascination with someone's feet when I should be filming their face. Sometimes it's uncooked filmmaking and it challenges the viewer to accept or reject it. But it's not smug. Smug documentaries suck.

JR: How did you approach the concert shoots? What type of look were you going for?

AC: I never got used to the process of sound checking for the concert, and then spending a few hours in nervous limbo until the performance. Most musicians get tipsy in this downtime and this shared drunkenness became the chief stylistic influence in the concert sequences. Lots of performers have told me that the 'correct' amount of alcohol gives a concert an edge without losing coherence, and I think the same was true for the filming. I found I filmed most of them with a combination of extreme close-ups and extreme wide angles. This is why I always think of the camera as having an idiot, child-like gaze... some of the time marvelling at the bigger picture, other times getting fascinated by an intimate detail such as Two Tears' facial expression of angry euphoria as she sings her nihilist classic 'Shit Fucking Job'.

JR: I found the film strangely decontextualized insofar as apart from one brief reference to "Sheffield" by Thomas Truax and Duracell's drive through France I didn't know where the gigs were taking place. I got the sense of almost directionless travel punctuated with brief concert encounters...was this intentional?

| Honkeyfinger |

Two of the concert scenes in the film do have a second back-up camera - a twenty quid security camera with a fisheye lens, just to give me a bit of reassurance in case I had a meltdown and filmed complete nonsense with my camera. But all the rest of the film is shot with a solitary gaze. There is actually quite a lot of editing in the music scenes... songs have verses so you can film vocals on one, guitar on another and so on, and edit it together to look like one piece. The audiences are definitely in the background in the concert scenes, loitering in the sepulchral gloom. I wasn't interested in vox popping audience members for what they thought - people watching the documentary can make their own decisions as to whether the music is any good or not. But also, with all the one-man bands I chose to film, I strongly got the impression that they were not playing to pander to the audience, they were playing as part of a personal journey for themselves. They had all reached a stage of musical evolution where, to play their own original compositions, they had moved beyond the possibilities of collaboration. If an audience enjoyed it, that made it even better, but that was not the point. Their music and performance have purity of intention, but with that indefinable atmosphere of oddness that you get when you spend too much time on something by yourself. I think the same can be said of the film.

JR: So given all the hardships and weirdness then, what do you think is the main motivation driving people to do this?

AC: I'd describe the film as a study of why human beings are driven to be creative despite the hardships that life erects in their way. One-man bands are the medium to investigate this idea. And I think the answer is reflected in the form of the film. Life is generally a bland and comforting monotone - in this case, foggy motorways, lukewarm cups of coffee, curmudegeonly cats, hungover loneliness. But every now and then you can break up the greyness with moments of startling, orgasmic intensity - for the one-man bands, the sublimation of hardships into the highs of performance. That's why it's all worthwhile.

2015/08/05

Maps, Territories and Lotusland

Last week I took part in the final night of the Lotusland residency at Changing Spaces, following the kind invitation of Jo Brook.

Lotusland is an open studio residency devised by artists Philip Cornett and Paul Kindersley. Billed as "a space to nurture a utopian yearning of a queerness that is not yet here", Lotusland channels the aesthetics of Jack Smith into a series of vibrant and subversive works across a variety of media.

The performance evening involved installations and video screenings from the artists, plus performances by Richard Dodwell, Jamie Ashman, Tom Tyldesley & Eve Avdoulos.

Bad Timing installed Self-Assembly, their mobile 'possible space' that functions as a venue-within-a-venue whenever and wherever it manifests. Projected inside Self-Assembly on this occasion was my video about William Burroughs, Territories (2015).

Territories was designed as an installation piece to tie in with the themes of the evening. I was ably assisted in the making of the video by Evie Salmon who provided the brilliant narration. On the night, the programme notes used the following outline:

Combining images and field recordings from

Scroll down for a series of images from the show.

|

| Still from Territories (2015) |

|

| Self-Assembly installed. |

|

| Self-Assembly inhabited. |

Labels:

counterculture,

events,

film,

recording

Strange Dimensions

Jack Hunter, esteemed editor of Paranthropology has just published Strange Dimensions. This anthology features some of the best writing to have appeared in the journal to date. I'm happy to say that 'Playback Hex', my essay on Burroughs, magick and the Moka Bar has been included as part of the selection.

Paranthropology is a brilliant journal that explores paranormality from a productive interdisciplinary perspective. Its very much in line with the ideas an aims of Exploring the Extraordinary, English Heretic and The Alchemical Landscape. All the issues published thus far are online. Together they make a fantastic resource for anyone interested in paranormality and occulture.

Explaining the anthology Hunter states:

It is from the paranormal’s multifaceted nature that the title of this book takes its meaning. Throughout its pages we encounter, time and again, talk of a wide variety of dimensions, levels and layers, from social, cultural, psychological and physiological dimensions, to spiritual, mythic, narrative, symbolic and experiential dimensions, and onwards to other worlds, planes of existence and realms of consciousness. The paranormal is, by its very nature, multidimensional.

Jeffrey J. Kripal, (author of Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred) adds this:

Once again, Jack Hunter takes us down the proverbial rabbit hole, here with the grace, nuance and sheer intelligence of a gifted team of essayists, each working in her or his own way toward new theories of history, consciousness, spirit, the imagination, the parapsychological, and the psychedelic. Another clear sign that there is high hope in high strangeness, and that we are entering a new era of thinking about religion, about mind, about us.

You can order a copy of the book here. Thanks and congratulations to Jack for putting this project together.

Paranthropology is a brilliant journal that explores paranormality from a productive interdisciplinary perspective. Its very much in line with the ideas an aims of Exploring the Extraordinary, English Heretic and The Alchemical Landscape. All the issues published thus far are online. Together they make a fantastic resource for anyone interested in paranormality and occulture.

Explaining the anthology Hunter states:

It is from the paranormal’s multifaceted nature that the title of this book takes its meaning. Throughout its pages we encounter, time and again, talk of a wide variety of dimensions, levels and layers, from social, cultural, psychological and physiological dimensions, to spiritual, mythic, narrative, symbolic and experiential dimensions, and onwards to other worlds, planes of existence and realms of consciousness. The paranormal is, by its very nature, multidimensional.

Jeffrey J. Kripal, (author of Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred) adds this:

Once again, Jack Hunter takes us down the proverbial rabbit hole, here with the grace, nuance and sheer intelligence of a gifted team of essayists, each working in her or his own way toward new theories of history, consciousness, spirit, the imagination, the parapsychological, and the psychedelic. Another clear sign that there is high hope in high strangeness, and that we are entering a new era of thinking about religion, about mind, about us.

You can order a copy of the book here. Thanks and congratulations to Jack for putting this project together.

2015/08/04

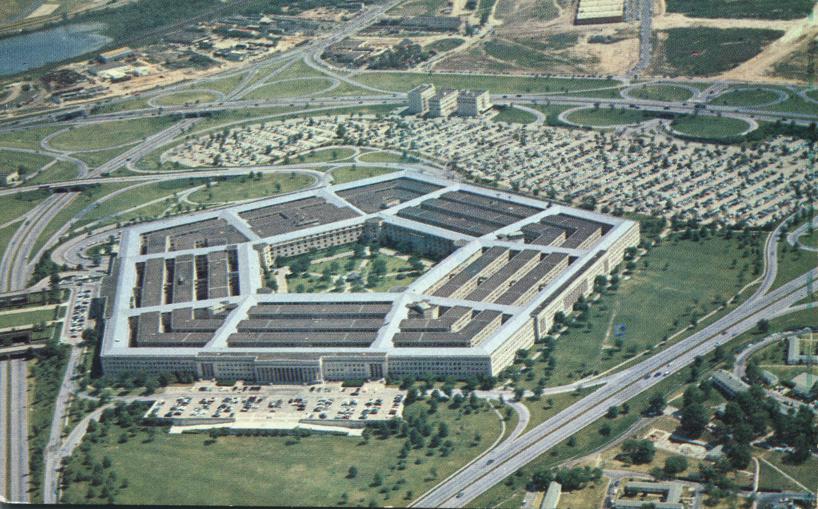

Postcard from the Pentagon

A city in itself, the Pentagon at one time during World War II reached a peak strength of nearly 35,000 employees. Its huge Concourse is operated principally as a shopping centre, including everything from a flower shop to a Washington department store. This huge building is in Arlington, Virginia.

The card was sent to England from Washington in April 1971 and contained the following note:

Have arrived in Washington. We landed about 4.30 on the same day. Weather very cold but dry: 19 degrees. I forgot my tapes. Please will you send them, especially the one in the white box. I went to work today. The company has got the contract on the atomic power station. Handwritten texts about atomic contracts are hard to ignore. That said, I find myself giving more thought to those tapes. What was on the tape in the white box?

It turns out that this particular printing - postcard 'PE-91' - has a certain amount of resonance within the conspiratorial aether, the field of Discordianism to be precise. In 1964, Kerry Thornley (aka Omar) sent the card to Greg Hill (aka Malaclypse the Younger). According to Adam Gorightly who discusses the correspondence in A Postcard from the Five Sided Temple, Thornley had "toyed with the idea of taking out a post office box at the Pentagon (if that’s even possible) and making it the official address of the Discordian Society headquarters."

*

2015/07/09

Underworld

Another piece from another notebook: documentary evidence

pertaining to an event organized in 2006. Followed by some brief supplementary

notes.

A tip of the hat to friends: the good Drs. Ashford, Brown

and Pender.

*

In March 1967 International Times, London’s premier

‘underground’ publication was subject to a police raid following a complaint to

the Department of Public Prosecution. In protest against this ‘piece of classic

intimidation’, poet Harry Fainlight roused various staff members and supporters

into staging an impromptu happening, ‘The Death of IT’. Spilling out from

UFO, a nightclub linked to the newspaper, several ‘pallbearers’ carried a

coffin containing Fainlight down Tottenham Court Road and onto Charing Cross.

They were following a route which would noisily weave through Trafalgar Square

and Whitehall eventually arriving at the Cenotaph to meet an assembled group of

photographers and journalists. In addition to the press this colourful, traffic

disrupting group also attracted the attention of the police. According to

author, musician and one time IT editor, Mick Farren, a confrontation was

avoided by the happening participants escaping into a tube station, thereby

getting off the ‘all too historic streets and causing the plods a good deal of

jurisdictional confusion’. Farren continues:

[…] the underground decanted into the Underground and

rode around with coffin and noise spreading alarm…At first we rode at random,

but with a pigeon-like hippie homing instinct we ended up circling the Circle

Line until we arrived at Notting Hill Gate where we re-emerged into the surface

world and began to wend our way north up Portobello Road, to the obvious

displeasure of the market traders who had just set up for Saturday, the big

business day.

Farren shows the tube offering a space conducive to the

carnivalesque aims of the happening. The retreat is not so much an admission of

defeat, a loss of the attacking impetus as it is a movement into psychogeographical

‘play’. The circling and the eventual wormhole-like re-emergence represent an

effective negotiation of various surface-based restrictions through a

non-standard experience of London’s transport system. The gravitation described

thus suggests that there is perhaps more than mere ‘semantic coincidence’

linking the word ‘underground’ as a spatial concept to its role as a cultural

signifier.

It was this intersection and its multiple permutations which

formed the focus of Urban Underworld, an international conference held at the

University of Cambridge in September 2006. Responding to the general subject

rubric of ‘London’s social, spatial and cultural undergrounds from 1825 to the

present day’, Eighteen speakers presented on a variety of topics including;

Jack the Ripper, Quatermass, Iain Sinclair, Mark Augé, Creep, Alexander

Trocchi, Henry Meyhew, narratives of descent, criminal slang, The Wombles and

others. A performative element was also incorporated with the event concluding

with a special happening featuring Michael Horovitz, Ian Patterson, free jazz

quartet Barkingside and films by Rod Mengham and Marc Atkins. The event aimed

to highlight potentially unexpected points of overlap between literary,

cultural and historical perspectives of the underground in its various

manifestations.

*

Spatial metaphors seen to proliferate when considering

notions of the counterculture: underground, subterranean, marginal, periphery.

Associated terms like ‘heathen’ spring to mind with its combination of theology

and geography. To be out on the heath means to be ‘outside’ both in terms of a

physical position and a subject position. Trocchi understood the normative

binary at play in these distinctions. Hence, the Sigma project aimed towards a

totalization of the spontaneous activities described by Farren. Trocchi wanted

the ‘underground’ to be rendered almost indistinguishable from its opposite so

as to participate in an efficient ‘outflanking’ rather than a frontal attack.

There’s a similar scene in Kerouac’s Big Sur (1962) where Jack Dulouz finds

himself in a strange liminal zone. Walking back to San Francisco from Bixby

Canyon he feels cast out of his retreat but at odds with the flow of tourists

driving to the coast. He’s neither at the centre nor the periphery; the city

nor the sea, and is momentarily aware of the contingency of both spaces.

Neither has the oppositional silence that's posited at the start of the book as

a productive alternative, counterpoint and / or escape.

The oppositional structure of any ‘counter’-claim threatens

to negate the potency of its stance. As a label, the ‘counter’ is constantly

haunted by that which it seeks to oppose even if such ‘opposition’ takes the

form of rejection, flight or transplantation. In the meantime the centre is a

black hole: dense, oblivious. ‘Culture’ is the more operative and useful of the

combination. Raymond Williams offers sage counsel: “one of the two or three

most difficult words in the English language”. Let’s plough on anyway:

1. The independent and abstract noun which describes a

general process of intellectual, spiritual and aesthetic

development.

2. The independent noun whether used generally or

specifically which indicates a particular way of life, whether of a people,

period or group.

3. The independent and abstract noun which describes the

works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity.

And then there’s the link to the cultivation of plants, by

way of cultūra, ‘cultivating’, from colere ‘to till’. This root in tillage puts

a useful spin on the notion of counterculture and its possibilities, not least

because it highlights the presence within the term of concepts relating to

geography and materiality. To understand ‘counterculture’ in this light, leads

not to hypothetical spaces of alterity but different modes of cultivation

within a shared stretch of land. The recourse to utopian impossibility is still

easy, of course, (associative conceptions of hidden islands, enclaves and

untouched spots) but grounding the signification of the word in cultivation

rather than confrontation at the very least modifies a restrictive binarism. I

guess in this mode the notion of an ‘underworld’ ceases to act as a level

within a two-story model but begins to connote something akin to a substrate, a

kind of sedimentary matter: the material that underpins and constitutes a given

architecture. Such a model posits a reiterative language of counter activity

(re-structuring, re-organisation, re-constitution), as opposed to one that is

projective.

Nothing new.

2015/07/04

Terrorism

As part of the Peter Whitehead Archive project (2010-2013) I edited an edition of the screenplay for the 2009 film Terrorism Considered as One of the Fine Arts. The book included the full screenplay text, a series of additional essays and previously unpublished archival material.

See below for my introductory essay written for the volume.

*

The idea of a single

work existing in multiple editions is not new nor is it uncommon to see a work

move across multiple platforms via film adaptations and online versions.

However, in the case of Whitehead’s oeuvre the four works that carry the title Terrorism represent something akin to a

quartet rather than a single work and several supplements. They share themes but remain formally

distinct. They are connected but – certainly in the case of the novel and film

– can also be seen as stand-alone texts.

The matter is further

complicated by the fact that Terrorism, the novel, was written as the

first volume of Whitehead’s Nohzone trilogy, a set of novels that includes Nature’s

Child (2001) Girl on the Train (2003) and the ‘fourth’ novel of the

three And Death Shall Have no Domain Name (2007). Girl, the third

novel has just followed Terrorism, the first, into print. Terrorism,

the film, began as an adaptation of the second novel Nature’s Child

before incorporating into its final form aspects of each of the Nohzone texts.

As such, whilst the film uses the title of the novel, the novel is not the

‘source’ of the film.

Confused? You should be because that’s sort of

the point, not least because a major theme of Whitehead’s Nohzone project is

informatic and bibliographic proliferation. Between 1990 and 1999 Whitehead

published five novels that dealt in various ways with notions of autobiography

and textual reconstruction. From the attempt to complete an unfinished

psychoanalytic case-study in Nora and …

(1990) to the interception of ghostly conversation in BrontëGate (1999), Whitehead’s fictions are archives of memoir,

dream records, letters, diary entries and transcripts. With the completion of Terrorism, Whitehead took this concept

one step further and used the memoirs of ex-MI6 agent Michael Schlieman as a

main structural motif.

Schlieman

previously appeared as the investigate protagonist of BrontëGate but in Terrorism

he is said to have vanished whilst on assignment in Cumbria . The novel charts the

attempt of an equally ambiguous narrator to retrieve and analyse the memoirs

Schlieman has posted online. This fluid and ambiguous text includes letters,

journal entries, fictional scenarios, and (un) reliable passages of

autobiography. What emerges is a mise en abyme of texts within texts and

an impression of Schlieman as a constantly deferred, fractal identity, a

presence that is active within the writing but which never makes the full leap

from spectrality to embodiment. Nature’s

Child continues the investigation of the memoirs and uncovers Schlieman’s

destructive love affair with Maria Lenoir (a key aspect of the Terrorism film), whilst Girl on the Train couples the oneiric

interiority of the material with an extended plagiarism of the Kawabata’s novel

Snow Country (1947). And Death compounds the vertigo of

this whole editorial enterprise as it purports to be another possible sequencing of Schlieman’s

memoirs. A portmanteau text that uses sections from the three previous novels

it works as a ‘new’ novel which has possibly been imagined in the mind of a

reader adept in the art of hypertext linking.

Although there

is more narrative connection between the first three texts, And Death works as a signal of the

potentiality that underpins the rest of the trilogy. As each of the novels unfold,

the retrieved texts constantly accumulate to the extent that Schlieman’s

memoirs seem like a vast digital abyss. For both the narrator and the reader

who navigate this information there is little feeling of completion but rather

an impression of radical contingency; the sense that the texts which constitute

the novels could combine and recombine into further versions ad infinitum.

Whitehead’s Terrorism film maintains this fluidity.

Watch it and you’ll initially think you’re seeing a detective movie or

espionage thriller. Whitehead appears as Schlieman on assignment in Vienna and he circles

through the city’s tram lines in search of Maria Lenoir and her ecoterrorist

cell. However, as Schlieman’s drifting generates a complex web of

entanglements, all such generic expectations go out of the window. This is no

urban quest or sewer-chase but a descent into an informatic rabbit hole. Dense

with meaning, the film uses an associative cutting style in combination with an

allusive voice-over and an often obscure set of on-screen texts to create an

intricate and dissonant web of reference. Just as the Nohzone novels exist as

strange textual archives, so too does the structure of Whitehead’s Terrorism film emphasise its own status

as a videographic archive. As a non-linear narrative, the jarring energy of its

montage suggests that we are seeing only one of many possible records of

Schlieman’s movement through the city.

The point here

is that Whitehead’s Nohzone work is significantly performative. Whether working

in print, with video or online, Whitehead foregrounds the formal specificity of

his chosen media and closes the gap between representation and representational

frame. That’s to say, in the novel Terrorism,

Schlieman’s memoirs refer to Girl on the

Train which is of course the novel we read when we come to the third volume

of the trilogy. Similarly, when watching the film Terrorism, we may indeed be watching the film Schlieman purports to

be making as a cover for his operations in Vienna . In a curious act of manifestation it

is suggested that the Whitehead texts that we hold, watch or surf are not about

Schlieman’s memoirs but actually are Schlieman’s memoirs.

All of which is

a preamble to the questions posed by the present Screenplay volume. What exactly are you reading here? Is this a

dossier of material explaining the film and documenting its production or is it

a further iteration of the Nohzone project? Are you about to read Whitehead’s

screenplay or Schlieman’s? It would be tempting to go for the latter or just to

say “both” and leave it at that. However, this would obscure the book's role of exposition. It is offered as a supplement, but one that aims to

illuminate Whitehead’s work, particularly the Terrorism film, rather than extend the fictional Nohzone world.

As a point of

comparison one should look to the screenplay editions that Whitehead published

under his Lorrimer imprint between 1966 and 1969 as opposed to para-texts such

as And Death. In particular his

edition of Jean-Luc Goddard’s Alphaville

published in 1966 places the screenplay alongside Godard’s original treatment.

Whitehead is credited with the translation and also the “description of the

action”, because although he paid Godard for the rights to produce a book,

Godard had no actual screenplay to offer him. After making the deal Whitehead

had to sit with a print of the film and produce his own version. The situation

was much the same for the Terrorism

screenplay. Although (as the dossier included in this volume indicates)

Whitehead produced a wide range of drafts and outlines, the film was not made

in accordance with a pre-written text. Much of the dialogue was improvised

between the various participants and Whitehead developed scenes in situ. Terrorism is also a film that found its form in the editing room.

Working with a considerable amount of footage shot between 2007 and 2008,

Whitehead spent time experimenting with different combinations of voice, image

and text until he achieved the consistency he was looking for. As a result, the screenplay included in this

volume has been compiled in retrospect. Working closely with the completed

version of the film, the dialogue and on-screen texts have been transcribed and

a Whitehead-approved description of the action has been added.

The decision to

publish the text in this form alongside a range of other material was made as

part of the Nohzone Archive publishing and editorial project. This programme is

linked to Whitehead’s extensive private archive of films, texts and production

materials. The project came into operation shortly after Whitehead completed

the Terrorism film and has to date

produced two texts: Things Fall Apart

(2012), a two-volume edition of the journal

Framework dedicated to Whitehead’s life and work and ‘Selections from the

Nohzone Archive, 1965-1969’, an extensive section of the Adam Matthew Digital

anthology Rock n Roll, Counterculture

Peace and Protest (2013).

Specifically, the current volume should be seen as the natural extension

of the Terrorism dossier included in Framework 52.2 (see the list of

suggested further reading elsewhere in this volume for more details).

The Framework section contained a number of

essays on the film and an extract of the screenplay. What is presented in this

volume is the whole text which has been edited to a much more comprehensive

level of detail. All three chapters are here complete with extensive

annotations, full cast and crew information and two additional documents by

Peter Whitehead: ‘Synopsis’ and ‘Dramatis Personae’. Following this, the book

presents a dossier of previously unpublished material detailing the gestation

and composition of the Terrorism film

project. This includes Whitehead’s original outlines for the Nature’s Child film; his correspondence

with key participants such as Sophie Strohmeier, Samantha Berger and Manuel

Knapp; two texts by Strohmeier detailing (amongst other things) her working

partnership with Whitehead and a series of additional Whitehead documents taken

from the Nohzone Archive. An extract from the Terrorism novel has also been included in this section and the

volume concludes with two specially commissioned essays on the film by leading

Whitehead scholars, Stephan Kurz and John Berra. As with the screenplay

chapters all the texts have, where relevant, been annotated and introduced.

Particular care has been taken to highlight points of overlap between the

dossier texts and the screenplay chapters. It is hoped that this

cross-referencing will provide some insight into Whitehead’s creative process

by alluding to the movement of an idea from a notebook extract or early outline

into the completed film.

As the content

of the screenplay chapters evidence (and the notion of a film having a

‘chapter’ implies) Terrorism is a multi-layered, self-consciously

‘literary’ film. In fact ‘film’ is probably the wrong term to use. Whitehead

shot Terrorism on digital video and this medium has informed its style,

ambience and aesthetic. Certainly the numerous ‘holographic’ scenes of

Schlieman on the Vienna

tram, his face reflected in the window like a ghost, would appear significantly

less ethereal if Whitehead had used film-stock. The obvious portability of

video also allowed Whitehead to shoot on the move and experiment with

improvisation. Beyond this formal specificity, Whitehead has also referred to Terrorism

as a graphic novel rather than a ‘film’, precisely because he intends it to be

an artwork that one ‘reads’ rather than ‘watches’. See for yourself: the full

film can be viewed on the You Tube channel Plagiarisme.Inc. The three chapters

are text heavy and much of the significance generated on-screen comes from the

interplay between the word and the image. As such, watching Terrorism in three parts online is

preferable to seeing it in a single festival screening. One can move

chronologically through chapters 1 to 3 but there’s also the possibility of a

more associative movement across the film by viewing, pausing, revisiting and

moving between each of the posted videos.

This is the type

of rhizomic navigation Whitehead intended to encourage when he posted his

novels online within a dense network of hyperlinks. It’s also the movement that

his protagonists embark upon when attempting to retrieve, explore and

reconstruct the texts at the heart of each novel. Schlieman is engaged in a

similar pursuit through the streets and scenes of Vienna in Terrorism, and the Screenplay

has been designed to help the reader/viewer of the ‘film’ participate in a

similar sense of speculation. Read this book in conjunction with the film. Read

this book in dissonance with the film. It provides the most detailed and

comprehensive account of the film’s gestation and includes supplementary

material available nowhere else. There is no better map of the various pathways

and dead-ends that populate the Terrorism film. Conversely, there is

enough material in this book to allude to other possible versions of the

completed film. Keep in mind that reading is an act of interpretation and

interpretation invariably involves the creation of new narratives. This book

will help you understand Terrorism and it will also help you to create

your own speculative version. There is no completion. It never ends.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)