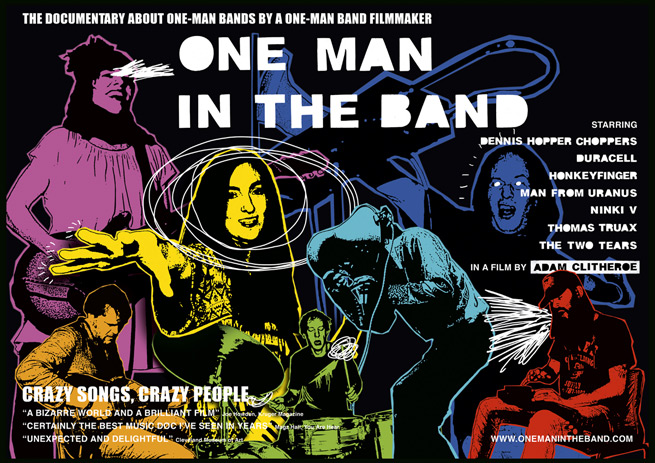

"One-man bands. Showmen, eccentrics, loners. This documentary follows a selection of contemporary musicians who play as one-person acts and discovers that, for them, music just sounds so much better when you make it all alone. Featuring musicians from the UK, France and USA and an awesome array of instruments ranging from theremins through to drum machines built from bicycle wheels, the film reveals the struggles that the performers have in balancing their public and private personas. As the music becomes ever more flamboyant and eccentric, so they find themselves retreating into loneliness and solitude. This is a moving and humanistic study of why people choose to be creative, filled with memorable musical performances, and achieving real intimacy between the one-man band filmmaker and his subjects."

It's obvious to me in retrospect that the subject was attractive because I was wondering if I'd ever make a film again, and whether I should bother. It's being drawn towards that mirror which, when you look into it, you'll be able to say "this is who I am". I hadn't thought about the film much more than that when a music promoter friend introduced me to Man From Uranus in a pub. He's this legendary one-man band, a Gulf War veteran from Florida washed up in the Cambridgeshire countryside who makes deeply eccentric music which sounds like Stockhausen writing kids' TV theme tunes. Plus he plays the theremin while wearing wellington boots on his hands. He invited me to a children's birthday party the next weekend and so the filming began. That's the great thing about the independent music scene - there's a real energy of "don't talk, just do it". On the other hand, independent filmmaking can be paralysed by procrastination - you don't want to piss away years of your life and bankrupt yourself by embarking on the wrong project.

AC: There are seven one-man bands in the film, three from the US, three from the UK and one from France. But I'm based in London which is one of the live music capitals of the world, so I picked up on most of them when they were passing through. I filmed on and off for around six months, for a few days here and there, travelling with them around the UK and in France. I'm not one of those American independent documentary makers who shoots hundreds of hours of footage and then has to employ a story consultant to make sense of the mess. I'm a lazy Englishman who filmed minimally for few evenings and weekends. As I said, I embarked on it with little thought about what the film would be. After I had a few weeks of filming under my belt the paranoia of what the hell was I doing started to kick in. Most of what I had shot had been filmed over a particularly grey and pallid winter, which sort of became an eighth character in the film, so it seemed appropriate to stop before spring kicked in, and to figure out what I had got.

AC: The film was all shot on a handheld progressive scan, square screen DV camera. My background is in 16mm filmmaking, and these video cameras give you results a bit similar to filming on Bolexes. The quality is not brilliant, but it has a texture and fluidity that is right for the subject. Plus you can fling the camera around without worrying about it too much. Portability of camera gear is an important consideration when you're filming a zero budget movie like this. Thomas Truax, a New York one-man band in the film, summarises it well. He builds elaborate mechanical instruments such as the Hornicator and Sister Spinster and uses them as surrogate band members. But if they don't fold up and fit in his suitcase, he can't get them on the train so he can't afford to tour so that's him finished as a solvent musician. Same for filmmaking.

AC: While I was editing the film, I read an interview with Mike Skinner, aka The Streets, in which he said he never mentioned specific locales in his songs because he wants them to appeal to people everywhere. If you have a caption on screen saying "Sheffield, 1am", whether you like it or not, you've focussed your audience's attention on a parochial narrative. If you're depicting an event of global significance, fine, time and date it, but if it's Thomas Truax locked out of his hotel room, don't. I like to think of the film as a frame of mind... it's a way of thinking that exists anywhere, anytime. Plus, the life of a one-man band is seemingly aimless... playing some small venue, packing up and drifting to the next town for the next gig. Identifying this meandering route would glamorise life as having some sort of structure and narrative.

One Man in the Band (2008) is one of the great cult music documentaries of recent years. Adam Clitheroe's heroic documentary sheds light on a fascinating musical underworld of sole performers playing on the hinterlands of the live circuit. In addition to featuring great music, it's an unexpected portrait of artistry and isolation. It's also a film that's capable of launching a thousand obsessions. When you see it, you'll find yourself scanning the gig listings, trying to track down some of the performers. The film has just had a digital re-release via Gumroad. Check it out. In the interview below Adam spoke to me about the process of making the film, the people who feature in it and the strange world he was granted acess to.

James Riley: How did the film come together?

Adam Clitheroe: The film, like many independent projects, arose out of desperation. I'd spent a few years trying to get feature documentaries off the ground. I wasted one summer waiting in fields in Mexico, hoping to meet friendly smugglers. Another time, I went to the Berlin Film Festival for meetings with Nigerian producers, which to my bemusement led to a hard cash offer to make a feature of my choosing. Naturally, the producers went back to Lagos and I never heard from them again. As time went on, the films I was trying to make became smaller and more adaptable to circumstance.

I became interested in making a documentary about performance - the idea that some people are driven to live a life of hard work and abstinent suffering, in return for a few moments of sublimation through performing. It seemed to be the flipside to the 'easy' celebrity culture that was dominating consumer media at the time - the idea that incredibly talented performers were trudging through a long dark winter of the soul, obscure and unremarked yet unwilling to give up on their ambitions. One-man band musicians seemed to be the purest embodiment of this sort of performer. Not novelty buskers, but people who take to the stage alone and compete with conventional bands at their own game, not compromising in the 'full band' sound even though they are solo. Can you name any famous, stadium-filling one-man bands? There are no household names. But there are hundreds of contemporary one-man bands out there working the circuit. Put some of them in a film and you're not going to end up with a celebration of acclaimed musical geniuses, but rather something more democratic: you've not heard any of these artistes, you listen to them and you decide whether or not they are any good.

Adam Clitheroe: The film, like many independent projects, arose out of desperation. I'd spent a few years trying to get feature documentaries off the ground. I wasted one summer waiting in fields in Mexico, hoping to meet friendly smugglers. Another time, I went to the Berlin Film Festival for meetings with Nigerian producers, which to my bemusement led to a hard cash offer to make a feature of my choosing. Naturally, the producers went back to Lagos and I never heard from them again. As time went on, the films I was trying to make became smaller and more adaptable to circumstance.

I became interested in making a documentary about performance - the idea that some people are driven to live a life of hard work and abstinent suffering, in return for a few moments of sublimation through performing. It seemed to be the flipside to the 'easy' celebrity culture that was dominating consumer media at the time - the idea that incredibly talented performers were trudging through a long dark winter of the soul, obscure and unremarked yet unwilling to give up on their ambitions. One-man band musicians seemed to be the purest embodiment of this sort of performer. Not novelty buskers, but people who take to the stage alone and compete with conventional bands at their own game, not compromising in the 'full band' sound even though they are solo. Can you name any famous, stadium-filling one-man bands? There are no household names. But there are hundreds of contemporary one-man bands out there working the circuit. Put some of them in a film and you're not going to end up with a celebration of acclaimed musical geniuses, but rather something more democratic: you've not heard any of these artistes, you listen to them and you decide whether or not they are any good.

|

| Man from Uranus |

JR: I guess some of these ideas fed into your own 'one man band' filming approach?

AC: Choosing to make the film entirely as a one-man band filmmaker was part of the process of subject and filmmaker finding reflection in one other. I had no funding so my initial worry was that I couldn't afford multiple camera shoots for live music scenes. I figured that if I filmed one-man bands, I would only need one cameraperson - myself. Plus I was very much aware that I had to gain the trust of the musicians in the film - they were allowing me to use their intellectual property of songs and performance. Approaching them as one well-meaning but slightly disorganised filmmaker meant that we found common ground very quickly and could share the chaos together. There is a slight paradox in that most of the one-man bands in the film are quite shy people - they can take the stage and wow a room of people, but strip them of their music and instruments and most of them want to evaporate. It's personal relationships that make interviews possible in these circumstances, and even if I could have afforded a film crew, it would have been a hindrance.

The other influence on the one-man band filmmaking approach was a 16mm short film I made beforehand, called Harder Faster Stronger Stripier. It was about my neighbour, an eccentric painter who is almost an outsider artist. The film was a curious observational piece, a skewed reflection of his world and a space for him to talk on his own terms. I think it had the same combination of the subject's hermetic creativity and idiot gaze of my camerawork that is found in One Man in the Band. It's one of my favourite short films I made. But only four people have seen it. We had the premiere in his front room, it was one of the most successful premieres I have ever had.

JR: How did you decide which artists to focus on?

AC: There are a lot of one-man bands out there, playing every genre of music imaginable. The first challenge is to figure out what you mean by 'one-man band'. It's a catch-all term, but you wouldn't refer to Bob Dylan playing his guitar and harmonica as a one-man band. So is it to do with the number of instruments you play live at the same time, or is someone strumming along to a backing tape also a one-man band? I figured that doing some sort of taxonomy of one-man bands would not make a very interesting film, so for me it became more important to find those people who, in their own minds, are one-man bands. They might not use the actual term, but they think of themselves as full bands and take to the stage to celebrate the joys of noise accordingly.

That principle established, it was a case of hanging out in lots of backstreet gigs and seeing which one-man band performers clicked for me. If you have seen someone play and you have seen something deranged and magical and unique and exciting in what they do, that motivates you to introduce yourself as a filmmaker and persuade them that you have something to offer back. So I guess that the people who made it into the final film were the ones I liked a lot as people and felt a personal connection. The only limiting factor was that some one-man bands are permanently touring and I couldn't afford to keep up with them. I would have loved to put Bob Log III in the film. He's this insanely fast slide guitarist from Arizona who wears an Evel Knievel jumpsuit and a motorcycle helmet with a telephone receiver glued to it. I filmed a gig with him at the Spitz in London and he drove the crowd into a baying mob - incredible. But then he was out of the country the next minute and I had no cash to follow.

One slightly disturbing aspect was that, as shooting progressed, it became clear that the majority of musicians I was filming had very tumultuous personal lives and were in the process of divorcing and separating. I wasn't aware of this beforehand, but when you build this intimate one-on-one relationship with your subject as filmmaker, you become privy to all sorts of personal stuff. Since all this pain and anguish seemed to fall in the brief period for which I was filming, I became worried that I was a bit of a jinx. But really, I think that for some of the musicians, the fact that they were having a rough personal time was subconsciously why I was attracted to filming them. There's this sense of wearing your nerve endings on the surface, of your emotions having been roughly sandpapered, that gives you this peculiar intensity and clarity in the way you present yourself. I don't think it's necessary to be jilted to be a successful one-man band, but that trauma perhaps amplifies certain traits of driven loneliness shared by one-man bands. After all, throwing yourself into your art absorbs the pain of separation.

JR: Could you sketch out some of your working methods? How long did the shooting take? How long did you spend travelling with the artists?

|

| Ninki V |

I did try to film the rhythms of life for the one-man bands. Because I didn't have prescriptive ideas I was trying to project into the film, it seemed appropriate to film whatever they were doing when I was with them, regardless of the banality. I didn't want the movie to be a series of highly structured talking head interviews, but then realised I had to interview them a little bit as they were alone on camera and they wouldn't talk at all otherwise. So the film is a series of offbeat chats on location, interspersed with the debris of everyday life. I especially like the scenes with some of the artistes such as Ninki V and Dennis Hopper Choppers in their homes. Someone else's domestic interior is your own vision of insanity.

One of the weird things in the editing of the film was the complete eradication of myself. While shooting, I hadn't really decided whether I would be in or out of the film as an off-camera presence. But because the film in post-production became quite strongly an atmospheric piece, being aware there is always someone else present in the scenes became a distraction. So I faded away and became invisible, like those figures in Soviet history airbrushed out of photographs. All that is left of me is the idiot gaze of that camera and an occasional eccentric spasm of editing.

JR: Man From Uranus seemed to be the fulcrum of the film. Was this because you found him perhaps the most interesting?

AC: Man From Uranus plays a pivotal role in the film. All of the seven musicians are very different personalities and play very different music, ranging from growling blues stomp to hurricane drum solos. But it’s safe to say there's no one else like Man From Uranus in the musical firmament. He plays a range of antiquated analogue electronica from theremin to reel-to-reel, producing a sort of bastardised lounge music on steroids. I think he represents an important aspect of one-man bandship because he's the one who most overtly considers music-making an artform, placing himself in the role of brilliant but odd outsider artist. Indeed, his antics with wellingtons and beep hats make perfect sense as performance art. On top of that, he is incredibly eloquent about his upbringing in the States by libertarian hippies and doom-mongering Baptists and his traumatic experiences in the US military. His musical journey represents some sort of quest for self-worth on his own terms. In the film, he represents the shift from presenting these weird and wonderful one-man bands as entertainers to a more searching questioning of what is it in the human condition that drives some people to be creative. Plus, he's a lovely guy who wears slippers all the time, even in winter snowstorms.

JR: Couple of technical questions: because you were working on your own what was your set up? What type of camera did you use and how did you approach recording the live sound at the concerts you shot?

|

| Duracell |

Recording live sound at the concerts was an extreme challenge. Usually there's an array of sound engineers making sure the audio is good for music television, whereas I was on my own, filming, taking stills and getting legal releases all at the same time. I'd turn up with the musicians to sound check, try and persuade the venue sound people to let me have a feed from the mixing desk, and then get another microphone set up in case that sound screwed up during the performance. A lot of these one-man bands are insanely loud... I think it's part of the compensation for being just one person on stage. The French drummer Duracell triggers synth loops from switches around the edges of his drum kit while he drums in the style of Animal from the Muppets. The amplifier he uses was liberated from a Meat Loaf tour in the 70s, and he produces this overwhelming tsunami of noise. The best way for me to get something useable was put a radio clip mic on him and put as many plugs as possible into my own ears so I could get close enough to film.

Having said that, I think it's far better to have the 'raw' music recording in this film than the over-sanitised live music you hear on TV which sounds like it's coming off a CD. Live music should sound live, and as Honkeyfinger said to me after hearing his swamp rock in the film, if it's gnarly that's a good thing. I think it's an important part of the one-man band experience that mistakes and blemishes become part of the performance. There are no other band members to hide behind, it's just you and the audience, and audiences tend to be much more forgiving of errors than they might be for a full band. In the same way, I left a lot of 'blemishes' in the film edit - wildly expressionistic camera zooms, an inexplicable fascination with someone's feet when I should be filming their face. Sometimes it's uncooked filmmaking and it challenges the viewer to accept or reject it. But it's not smug. Smug documentaries suck.

JR: How did you approach the concert shoots? What type of look were you going for?

AC: I never got used to the process of sound checking for the concert, and then spending a few hours in nervous limbo until the performance. Most musicians get tipsy in this downtime and this shared drunkenness became the chief stylistic influence in the concert sequences. Lots of performers have told me that the 'correct' amount of alcohol gives a concert an edge without losing coherence, and I think the same was true for the filming. I found I filmed most of them with a combination of extreme close-ups and extreme wide angles. This is why I always think of the camera as having an idiot, child-like gaze... some of the time marvelling at the bigger picture, other times getting fascinated by an intimate detail such as Two Tears' facial expression of angry euphoria as she sings her nihilist classic 'Shit Fucking Job'.

JR: I found the film strangely decontextualized insofar as apart from one brief reference to "Sheffield" by Thomas Truax and Duracell's drive through France I didn't know where the gigs were taking place. I got the sense of almost directionless travel punctuated with brief concert encounters...was this intentional?

| Honkeyfinger |

Two of the concert scenes in the film do have a second back-up camera - a twenty quid security camera with a fisheye lens, just to give me a bit of reassurance in case I had a meltdown and filmed complete nonsense with my camera. But all the rest of the film is shot with a solitary gaze. There is actually quite a lot of editing in the music scenes... songs have verses so you can film vocals on one, guitar on another and so on, and edit it together to look like one piece. The audiences are definitely in the background in the concert scenes, loitering in the sepulchral gloom. I wasn't interested in vox popping audience members for what they thought - people watching the documentary can make their own decisions as to whether the music is any good or not. But also, with all the one-man bands I chose to film, I strongly got the impression that they were not playing to pander to the audience, they were playing as part of a personal journey for themselves. They had all reached a stage of musical evolution where, to play their own original compositions, they had moved beyond the possibilities of collaboration. If an audience enjoyed it, that made it even better, but that was not the point. Their music and performance have purity of intention, but with that indefinable atmosphere of oddness that you get when you spend too much time on something by yourself. I think the same can be said of the film.

JR: So given all the hardships and weirdness then, what do you think is the main motivation driving people to do this?

AC: I'd describe the film as a study of why human beings are driven to be creative despite the hardships that life erects in their way. One-man bands are the medium to investigate this idea. And I think the answer is reflected in the form of the film. Life is generally a bland and comforting monotone - in this case, foggy motorways, lukewarm cups of coffee, curmudegeonly cats, hungover loneliness. But every now and then you can break up the greyness with moments of startling, orgasmic intensity - for the one-man bands, the sublimation of hardships into the highs of performance. That's why it's all worthwhile.