|

As seen on the return journey.

|

28/06/2019. Been quite a while since the

last trip. Parking up now and waiting. Across the road there’s a clutch of

trees jutting out of the verge. The sun is high and is flickered by the

branches. In the bleed the video shimmers as it struggles to pick out the

detail.

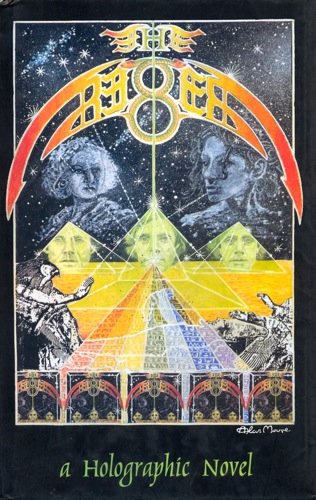

Peter Whitehead’s The Risen

(1994) follows three characters – a crystallographer, an actress and a sculptor

– as they retreat to an isolated house in Cornwall. There they entangle

themselves in a sequence of intense, shamanic rituals: initiatory processes that

help them establish contact with John, the novel’s fourth character. John is a

Syd Barrett avatar, a psychonaut who has vanished leaving only a set of coded

messages behind. Throughout the novel he exists as an absent presence, an

entity who haunts the text just as much as he haunts the characters. Reading

like a smart-drug infused cut-up of H.P. Lovecraft and Jacques Derrida, The Risen unravels following the

progress of these personalities as they intersect, interfere and entangle with

each other, on numerous planes at once.

In The Risen, what happens on

one plane of existence influences those that stand in horizontal and vertical

proximity. The past and the present; the ‘real’ world and the afterlife; the

textual realm and the digital; they each collide and intermingle as the novel

gradually works its way into a mind-bending field of synchronicity and

simultaneity. Whitehead called this structure holographic. He likened The

Risen to a half-silvered mirror through which a laser is fired and which

produces, in the spaces between, a ghostly, two-dimensional image that appears

also to stand in three dimensions.

|

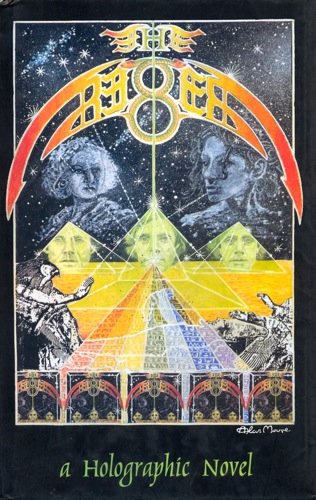

| 1997 paperback edition |

|

| 1994 hardback edition |

28/06/2019. On the turn-in there was a familiar figure

strolling through the village. Recognized the gait and stance. Time to consider

my own. Head in to the place, down a path of heavy humming. Mixed feelings,

most to do with the reasons for the absence. But this much said, such

preparations are, and should be, for naught because – of course – it is not my

day.

Whitehead wrote many novels, but during the time I knew him – first as a

friend, then as a collaborator and then, for a while (2009-2014) as director of

his archive – he consistently referred to The

Risen as his touchstone work, a book that summed up how he wrote, why he

wrote and what he wrote about. The novel had its origins in Nighttrip (1969) an unproduced

screenplay about a long, mystical drive into the heart of an occult system.

Other prose versions followed as Whitehead moved through the 1970s and into the

1980s via different countries and different lives: film-maker, writer,

falconer. The version published in 1994 contained aspects of these prior

iterations but it also drew on the heady underground atmosphere of the

early-1990s, becoming in the process something of an unconscious lightning rod

for the neo-counterculture of the late twentieth century. The cult independent

publisher Creation Books initially had plans to issue The Risen, it was listed and is still carried by Midian Books and when

published by Hathor it generated interviews and features in the likes of Esoterra magazine. Whitehead read from The Risen alongside Iain Sinclair, Chris

Petit and Brian Catling at Disobey’s Subversion

in the Street of Shame event in July 1994 and references to books like Robert

Temple’s The Sirius Mystery (1976) –

the kind of speculative Egyptology that reached a critical mass of popularity

at the turn of the millennium – peppered the text. In short, it was exactly the

kind of novel you could read alongside Clive Prince and Lynn Picknett’s The Stargate Conspiracy (1999).

Another important influence was Rupert Sheldrake’s concept of morphic

resonance, an idea he outlined in two Whitehead favourites, A New Science of Life (1981) and The Presence of the Past (1988). In

short, morphic resonance describes a form of collective memory in which self-organising

systems pass on information through patterns of repetition, cycles that appear

able to extend influence across vast swathes of space and time. Sheldrake draws

on plant sciences and an array of animal behaviour to explain this model of

inheritance and to make a case for its significance as regards such doubted

phenomena as telepathy. In The Risen,

Whitehead used a similar concept to explain the psychic communication between

his ‘earthly characters’ and the vanished, transformed intelligence calling

itself John. He termed it ‘The R-Field’, the ‘R’ standing for ‘reincarnation’, amongst

other things. For Whitehead, this described an aether-like medium in which the

trans-dimensional and trans-temporal events of the novel take place. Whitehead

also gave the R-Field a powerful symbol within the text, a location that the

narrative obsessively returned to: a small inland

clearing of trees within the Cornish landscape that he called, simply, the copse.

28/06/2019. After

the Church, the plan was to drive back round the old haunts – the first house,

then the car park island with its smattering of shops. It's full when I get

there so there’s no photo. The house is also hard to find, even though

everything seems a lot smaller than I remembered. The very first visit to the

house had been a ghostly pursuit, the rest a kind of pupillage or initiation.

The copse is a thin space, a locus in which the various

planes that flow through the novel converge into a point of intersection. As

the novel progresses, it becomes clear that the copse is the place where John

disappeared, or rather moved on. Initially,

Whitehead’s use of the location recalls John Michell’s speculations on leys and

ceremonial mounds as meeting places between men and gods. That said, for

Whitehead, the copse does not relate solely to ideas from the Earth Mysteries

scene. He offers it as an interstitial location, the novel’s holographic

centre; a site at which one thing becomes another and in between a third space

momentarily opens. As describes in The

Risen, it is the letter ‘r’ which separates the word ‘corpse’ from ‘copse’.

One word contains the other even when it is not articulated. So too with John’s

progress in the novel. He’s not there, but neither is he entirely absent. His

presence ripples through the text, felt and recognised but never fully

manifest. There is no ‘return’ from the elsewhere but an increasing

re-enactment on the part of those who remain; a growing awareness that their

exploration of a set of interconnected texts is a re-plotting of John’s

narrative. In the esoteric world of The

Risen, this involuted unfolding of one narrative within the space of

another is intended to describe nothing less than a system of reincarnation.

28/06/2019. Leaving

the place, I’m circling: I’m driving round the same network of tight,

overcrowded roads that used to lead from one of the houses to another. We

worked at a few different locations dotted around the area and they formed a

kind of circle around the town bordered by the vestigial countryside. New

housing developments had ornamental lakes hewn out of the ground, pushing back

the tree line. Going through the motions, other journeys come back like the

time I drove there blind in thick fog. Others I spoke to reported appearances

up and down the road. Signalmen at the crossroads jostling with phantom

hitch-hikers. On more than one occasion, when driving with him, he would point

to a gathering of trees and announce that it was the copse. He seemed to be in

search of it. Seen from the moving car, these isolated alcoves blurred into

strange shapes: static points in the landscape lost in flicker. Difficult to

find on a return journey and even harder to capture in an image. The video

would shimmer as it struggled to pick out the detail.

*