Recently I took part in the Anglia Ruskin conference, J. G. Ballard and the Sciences. Organised by Jeanette Baxter and featuring Christopher Priest, Fay Ballard and a range of excellent international speakers, the event was a really successful investigation of the intersections between Ballard's writing and parallel fields of investigation. I spoke about Ballard and sensory deprivation, a topic I've been interested in for a while. It was good to outline these ideas and also to reflect further on some of my recent experiences in floatation tanks: I'm all in favour of experimenting on the self, as it were. My thanks to Jeanette Baxter for including me on the programme. A big shout out should also go to the good people at Cambridge's Art of Float: if you want to experience the type of things John C. Lily and Paddy Chayefsky were talking about, check them out.

I've added my abstract for the talk below. The title comes from e.e. cummings' account of imprisonment, The Enormous Room (1922), a useful point of comparison with Ballard's 'The Enormous Space' (1989).

*

The

Enormous Room: J.G. Ballard and Sensory Deprivation

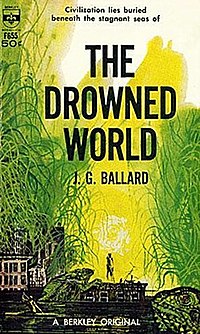

In The Drowned

World (1962), the ecological regression of the natural landscape to a Neo-Triassic

state prompts a similar “archeopsychic” shift in human psychology. Consistent

with Ballard’s other post-apocalyptic scenarios, access to these “ghostly

deltas” of inner space is welcomed by the novel’s characters, particularly the

biologist Robert Kerans.

For John Baxter the “neuronic odyssey” of The Drowned World echoes the work of neurophysiologist John C. Lilly who, from 1954 onwards, conducted a series

of sensory deprivation experiments using enclosed floatation tanks. As Lilly

would go on to describe in The Centre of

the Cyclone (1972) sensory deprivation prompted “mystical states” and

allegedly enabled him to undergo a regressive anamnesis that permitted access

to deep genetic memory. Lilly’s work paralleled that of psychologist Donald Hebb

at Canada’s McGill University. Commissioned by the US Air Force, Hebb used

dark, sound-proof isolation chambers to simulate the withdrawal of sensory

stimuli from test subjects. Colin Wilson’s novel The Black Room (1971) drew on the McGill experiments whilst Paddy Chayefsky’s Altered

States (1978) took the visionary

aspects of Lilly’s work as its basis.

In the case of Ballard, language

and imagery redolent of this field of post-war experimentation appears across

his career, not just in The Drowned World

but also short stories such as ‘Manhole ’69’ (1957), ‘The Gioconda of the Twilight

Noon’ (1964) and ‘The Enormous Space’ (1989). In each case the lack of sensory

stimuli results in experiences of spatial, psychological and temporal

expansion.

After unpacking the link

between Ballard’s texts and the surrounding context of sensory deprivation, I

wish to mark out his thematic difference from the likes of Lilly, Wilson and

Chayefsky et al. While they variously

connect the experimental process to the discovery of a foundational human essence,

Ballard’s narratives plot movements towards the dissolution, negation and

reformation of human identity. In examining this representation of men in the

process of disappearing, this paper uses the literature of sensory deprivation

to interpret Ballard’s predilection for terminal identities framed as

transformative states.